When Ruhollah Khomeini, while visiting Iraq met with Muhsin Al-Hakim, he urged him to take action against the Baath regime who had just arrived to power in 1968. Al-Hakim is said to have replied: “If we took drastic measures people would not follow us. The people lie and follow their whims, they are in pursuit of their world desires”.

Here you have it, the ultimate difference between the old order and the new, between the aristocratic wisdom of Al Hakim and the genius intellect of Khomeini: using the new institutional and organisational technology to turn “people” into an “active”, useful political force. Ultimately, this required the reinvention of what is meant by “the people”. There were other known changes that separated the old order from the new. As Marx argued, capitalist modes of production led to unbridled resource accumulation, management, and acquisitiveness, and what comes with it in terms of social change and large-scale economic extractive systems. These were developing in parallel to, the formation of the modern state with its rule of law, bureaucracies, policing system and disciplining institutions that Weber, Foucault and others have explained in great details.

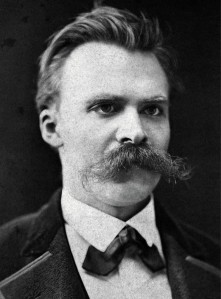

One overlooked visionary of “modernity” is Nietzsche, who saw the crux of the change located more specifically in our vision of “the human condition” or the relation between social classes. Nietzsche is prophetic as he could foresee that both the left and right side of the political spectrum, belonged to the same tradition triggered by the “age of enlightenment” but also as a remnant of a Christian (read Protestant) morality turned into populism.

Nietzsche’s warning is that this discourse of human rights, socialism, nationalism, equality, that reinvented our notion of “the people” had very revolutionary implications. The theorist of “the will to power” was ironically the earliest to be wary of modernity’s potential to abuse power and lead states to useless wars. His critique of democracy was very much along the line of Plato’s and based an elitist view of the different capabilities of humans to develop political skills.

In “the West”, Nietzsche was the last anti-mass-politics anti-populist thinker, the last of the old order (which stretched back to the Greeks and before). Somewhere else, Al-Hakim’s quote mentioned above is reveals a similar pre-modern understanding of the human condition. That is not too surprising given that he belonged to an uninterrupted lineage of a class of people, Shi’i “clerics”, who went back almost a millennium. In this old order, humans were comfortable with the idea that equality doesn’t mean anything and does not exist in reality. If anything, equality is a dangerous reality. As al-Hassan (the son of Ali bin Abi Taleb) is reported to have said in a cryptic way: “if all men were equal the world would have been destroyed”. But here equality means “having the same skills”, or “being similar”. Equality is not to be confused with Justice, which is the foundation of conceptions of the-living-together in the older order. Ironically, today justice is conceived as a stripped down version of the old notion, as “fairness”, to echo Rawls. While the modern legal and philosophical notion of equality has done wonders in terms of solving many “unjust” social phenomena, it also has put humans at the mercy of the technologies of the modern state.

Equality here is problematic because it involves an idea that we want to impose to an otherwise different reality. In reality, people have different capabilities, do different things and develop different skills. They also have different types of wealth, control different types of resources, all this relating to family, geography, history etc. Equality involves building a system that forces everyone to potentially receive the same kind of treatment but yet in reality do not. This involves erecting a wide series of institutions and technologies with unbridled power which although keeps the ideal of equality alive, in reality produces oligarchical systems in which influence and control of people and resources are in the hands of the few. Another difference in reality is that in the modern era the human condition is understood through a system of rights rather than through a system of duties and development of skills or ethics (that were ironically called “rights”). The older order that was based mostly on this paradigm was rejected because of the power abuses that ensued from it. But the new system is presenting unprecedented power abuses that are for the time being unaddressed.

Some may retort that Zionism was a secular ideology, yet the seriousness with which the Jewish movement treats passages of the Old Testament as part of the history of a political community is quite similar to what ISIS does with stories of the prophet and his companions, especially when it comes to relating these stories to a material experience involving the seizure of territory and management of population. In fact, the differences (how the religious uses secular textual technologies) as well as the similarities (what they actually do with it) can shed light on the peculiarity of state or other organizational formations in the Middle East.

Some may retort that Zionism was a secular ideology, yet the seriousness with which the Jewish movement treats passages of the Old Testament as part of the history of a political community is quite similar to what ISIS does with stories of the prophet and his companions, especially when it comes to relating these stories to a material experience involving the seizure of territory and management of population. In fact, the differences (how the religious uses secular textual technologies) as well as the similarities (what they actually do with it) can shed light on the peculiarity of state or other organizational formations in the Middle East.